"There is no good in the country of the Christians for a Muslim."

— Ayuba Suleiman Diallo, one of the most prominent enslaved West African Muslims. Writing in Arabic while enslaved in Maryland, he described the condition of Black Muslims in America in a letter home to his father, constituting possibly one of the first reflections of Islamophobia in the New World. (Source)

Letter from Ayuba Suleiman Diallo to his father, 1731–33

<aside> 📅 Join MMHI and MuslimARC this Tuesday, February 9 from 5:30-7pm for part 1 of their Anti-Racism 101 workshop, Social Impact of Racism and Learning ARCompetency. RSVP now to reserve a spot at the workshop. Details.

</aside>

Early Islam, which had been revealed to the Prophet ﷺ between 609 and 632 CE, could be traced back to its roots in North Africa, where it was introduced around 660 CE. Islam was earlier introduced during the first Hijra by Arab Muslims who arrived in Abyssinia (modern-day Ethiopia) in East Africa. They established the as-Sahaba Mosque in Eritrea, possibly the first ever in Africa.

By 1501, when Africans were deported to the New World, Islam in its orthodox Sunni form had established its strongholds in West Africa, initially in the first West African Muslim state of Senegal, and spread to bordering Mali and northern Nigeria.

Photo: Mark Cartwright / Ancient History Encyclopedia

The spread of Islam in West Africa was markedly peaceful, unlike the wars and conflict by which it spread in northern Africa. While a majority of people in Western Africa were non-Muslim, the increasing co-existence between non-Muslims and Muslims paralleled the growing religious diversity across the region. The 15th century witnessed a closer association between Islam and Sufi orders, with an emphasis placed on the personal relationship between man and God. The Qadiriyya, established by Abdul Qader Gilani (1078-1166), was the most extensive Sufi order in West Africa throughout the 19th century, encouraging a brotherhood linked “over geography, ethnicity, and social class”.

<aside> ❓ Reflect: Sufism continues to be widely practiced in areas around the world such as Turkey, India, Morocco, Senegal, and Sudan to name a few. In what ways do you see Sufism reflected in modern tradition and cultural practices?

</aside>

Studying the spread of Islam in west Africa in relation to the accompanied growth in literacy allows us to more deeply analyze the economic and cultural strength of West Africa’s “global market”. In addition to building ties with Maghreb, Egypt, and the Middle East, an exchange of theology, religious thought, and commerce was observed between kingdoms in Mali and Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria, to name a few.

While Mansa Musa may be the most common example of a leader whose travels and rule introduced a wealth of opportunities for the people of Mali, there are other lesser known leaders and scholars in western and northern Africa who valued literacy, and with it, Islamic principle.

Imam al-Maghili, an Algerian scholar, converted the ruling classes of the Hausa, Fulani, Songhay, and Tuareg peoples in West Africa to Islam. He served as a counselor to King Rumfa in Kano, Nigeria, which boasted three thousand teachers by the end of the fifteenth century, and authored a manuscript regarding Islamic law and its accordance with good governance.

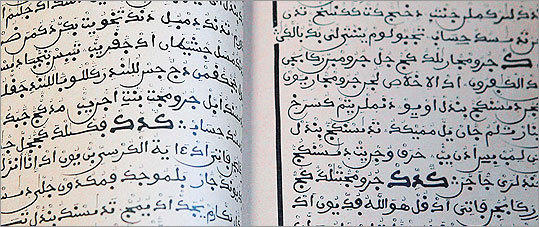

The Fulani in Bundu, a state in Senegal, and the city of Timbuktu established hundreds of schools to expand Islamic knowledge to the wider population. Many Muslims knew the Qur’an by heart, and a large proportion of Muslims learned to read and write in ajami, their version of the language transcribed in Arabic alphabet.

The Ajami script, which was used to write West African languages such as Swahili, Hausa, and Yoruba in Arabic script. (Jonathan Wiggs / Boston Globe)

By Ousmane Oumar Kane

Buy on Amazon

By Rudolph T. Ware

Buy on Amazon

Photo: Islamic Center of South Florida / YouTube

<aside> 🔦 Spotlight Dr. Ousmane Oumar Kane holds the Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Chair on Contemporary Islamic Religion and Society at the Harvard Divinity School and the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilization at Harvard University since July 2012.

Kane studies the history of Islamic religious institutions and organizations since the eighteenth century, and he is engaged in documenting the intellectual history of Islam in Africa.

Follow: Website

</aside>